An African Uprising: The story of Chilembwe and the 1915 rebellion against imperial Britain:

Story Summary / Synopsis

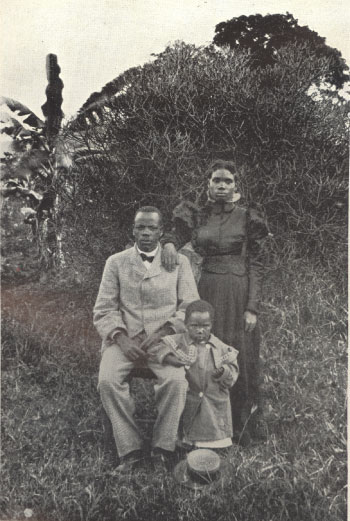

John and Aida Chilembwe and child.

In the late 1800s, in central Africa (now Malawi) there is great turmoil. The Nguni warriors, fleeing the brutal Shaka the Zulu king, have settled in the highlands and are making periodic raids on other tribes; Swahili Arabs and their African agents are capturing slaves and sending them to Zanzibar before some are shipped as far as Persia; and famine is recurring. The land is greatly troubled.

John Chilembwe, an ambitious young man, is born in this area. As one born with feet first, culture has it that he is destined for great things. All he needs is a ticket.

Due to the influence of the famous Scottish explorer David Livingstone, British Christian missionaries have settled into the area, followed by a motley crew of commerce people, farmers and of course, land speculators. There is finally some peace in the land. Young Chilembwe is fascinated by the new ways brought by the white man.

Chilembwe arrives at the door of the radical white missionary Joseph Booth with the letter: “Dear Mr Booth, you carry me for God. I like to be your cook boy”. Booth, against the wishes of most of the whites, believes Africans can rule themselves after the right training. In Chilembwe, he sees a very promising protégé.

Booth wants to take Chilembwe to the United States. But Chilembwe has to seek permission from his mother first. With fears of the cannibalistic white men across the oceans, the mother reluctantly agrees. In 1897, they sail to the new world, via the old world of Great Britain.

There Chilembwe meets racism at first hand. At one place, both he and Booth are stoned. And at the insistence of Africans Americans of the National Baptist Convention, Chilembwe and Booth part ways. Chilembwe is enrolled in a seminary college at Lynchburg in Virginia.

Chilembwe is in the US during the failure of the Reconstruction. He sees a different white man, a racist white man. But he also sees how the freed slaves are fighting back. And he hears of the legends of Nat Turner, and John Browne of Harper’s Ferry, tales that leave a strong impression on him.

Chilembwe graduates and returns home to what he thinks will be a heroic return. But he is in for a surprise. To the white settlers, Chilembwe is an African who is above his station. In a typical manner of his former mentor Booth, Chilembwe becomes vocal against the white rule. Issues mainly revolve around land tenure most of which has been taken by whites. He is also against Africans being sent to fight British wars.

He buys land and starts an industrial mission. His neighbour is the huge Magomero estates, owned by David Livingstone’s grandson and run by William Jervis Livingtone, a distant relation. William’s cruelty towards his workers is quite renowned. Moreover, when Chilembwe erects churches and schools on the vast farm, they are burnt down. In William, Chilembwe concentrates his anger against the whites in the country. And for William, Chilembwe becomes the archetypical ‘native above his station’.

Times are tough for Chilembwe: the funds from the US have stopped, he has lost a daughter, his licence for shooting elephants for ivory has been revoked by government, there is great famine in the land pushing more Africans on to his mission for help, he is losing his eyesight, and he owes a lot of money for the impressive cathedral he has built. But it is the First World War that proves the last straw. He writes a scathing letter to the newspaper of the day castigating the government for sending Africans to a war that does not concern them.

Chilembwe stages an uprising just months into the War. He plans to kill all white men in the country. His first target is William Jervis whose severed head is stuck to a pole. Two more white men are killed in the vicinity of Magomero. Another of his team is sent to Blantyre where, in John Brown’s style, they are to take break into an armoury and steal guns. That mission is botched. Government including the reserve soldiers retaliates and soon Chilembwe and his men are on the run. Chilembwe is shot two weeks later and most of his fellow plotters are rounded up and either shot or hanged.

Today, Chilembwe is still commemorated in Malawi, especially as a symbol of fighting injustice. His face appears on several bank notes in Malawi and he has his own holiday.